A walnut-sized bee with a wingspan of two and a half inches – about the length of a human thumb – may seem like something straight out of a science fiction movie. However, the Megachile pluto, or Wallace's Giant Bee, is not a figment of a movie writer's imagination, but a real insect that dwells in the Indonesian forests. While a few dead specimens of the bee have been discovered over the years, researchers have not seen a living one since 1981. Now, thanks to a team of dedicated American and Australian biologists, the magnificent bee has been photographed live in its natural habitat for the first time.

Measuring 1.5 inches long, or about four times larger than the honey bee, Wallace's Giant Bee gets its nickname from Alfred Russel Wallace. The British naturalist was the first to record the existence of the massive insect in 1858, while exploring the island of Bacan in Indonesia. In his notes, Wallace described the bee as “a large black wasp-like insect, with immense jaws like a stag-beetle."

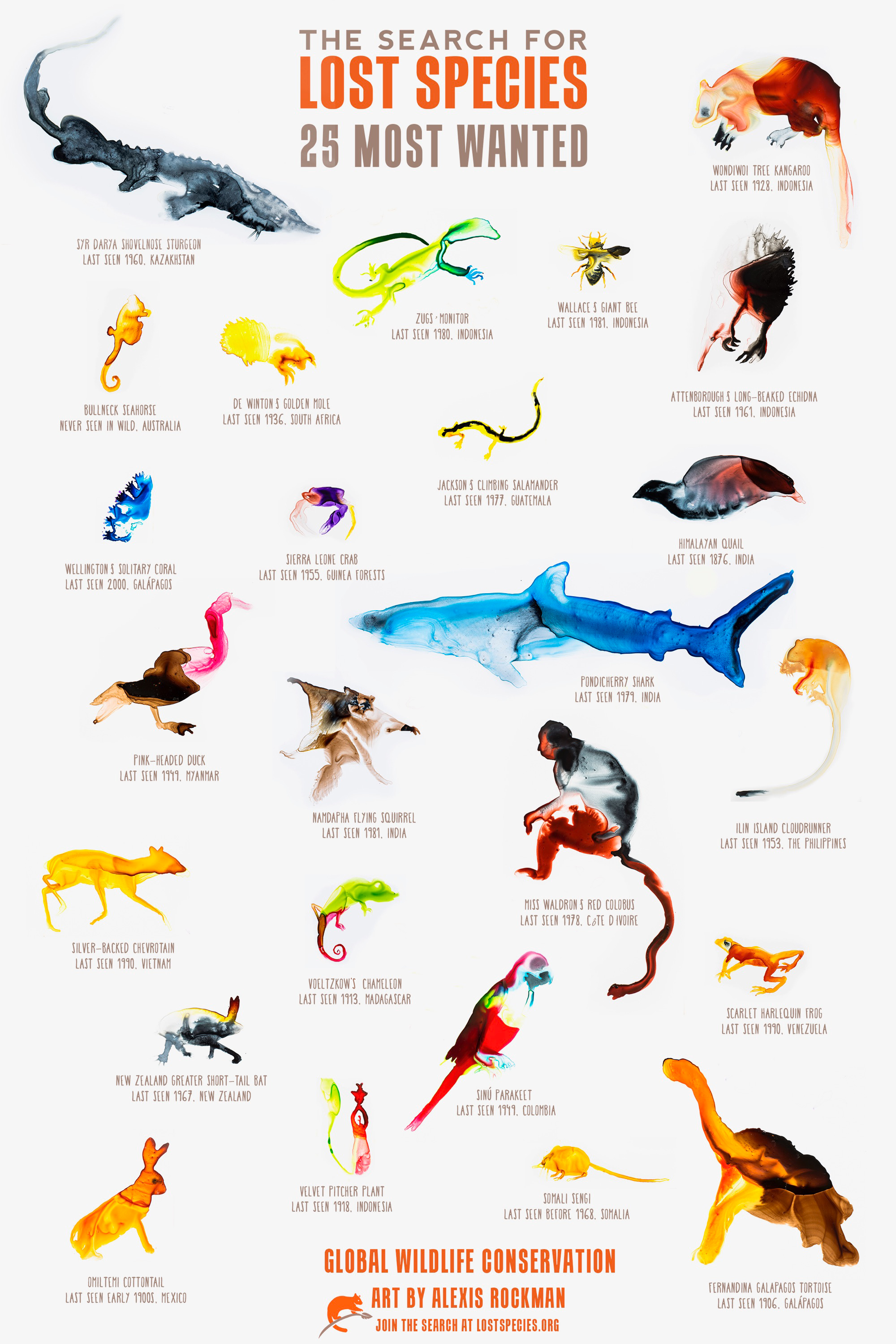

In 1981, American entomologist Adam Messer spotted the magnificent creature on three different Indonesian islands. He observed that the smart female bees, built their nests inside active arborealtermite mounds and lined them with wood chips and sticky tree resin to protect them against invading termites. Since then, many scientists have tried to look for the rare insect, but have had no luck. In 2015 the Global Wildlife Conservation placed Wallace's Giant Bee on its top 25 most wanted species list under their Search for Lost Species program.

American natural history photographer Clay Bolt first heard about the bee in the early 2000s. However, his desire to seek out the elusive creature in the wild did not begin until 2015 when the University of Princeton entomologist Eli Wyman showed him a preserved specimen of the insect. The photographer writes in his blog, "It was more magnificent than I could have imagined, even in death."

In January 2019, Bolt and Wyman teamed up with Canadian-Australian writer Glen Chilton and University of Sydney biology professor Simon Robson, to search for Wallace's Giant Bee in the Indonesian island of Ternate. The scientists, along with two local guides, spent the days trekking through the hot and humid forests seeking out termite mounds and observing them for about 20 minutes for signs of the insect. On the fifth and final day of their expedition, just as the team was losing hope, one of the guides noticed a termite mound on a tree, about eight feet above the ground.

When Wyman investigated the mound further, he noticed that the hole was a little more perfect and rounded than those on other nests. Even more exciting, the inside of the mound appeared to be wet and sticky. Almost sure he had stumbled upon the bee's nest, Wyman asked Bolt to take a look. The photographer says, "I climbed up next, and my headlamp glinted on the most remarkable thing I’d ever laid my eyes on. I simply couldn’t believe it: We had rediscovered Wallace’s Giant Bee. It was absolutely breathtaking to see this ‘flying bulldog’ of an insect that we weren’t sure existed anymore, to have real proof right there in front of us in the wild.”

After celebrating with the team for a few seconds, Bolt proceeded to photograph and videotape the bee, achieving his dream of being the first person to capture the insect live on camera. The photographer gushes, "To see how beautiful and big the species is in real life, to hear the sound of its giant wings thrumming as it flew past my head, was just incredible.”

Bolt and Wyman now hope to work with Indonesian scientists to find other specimens of Wallace's giant bees so more can be learned about the elusive insects. They also plan to work with conservation groups to ensure the protection of the magnificent species. Wyman, who fulfilled his life-long desire of seeing a rare species in the wild, says, “I hope this rediscovery will spark future research that will give us a deeper understanding of the life history of this very unique bee and inform any future efforts to protect it from extinction.” Finding the massive insect live in the wild has also renewed hope among researchers that more rare species are alive and well within the Indonesian forests.

Resources: globalwildlife.org, the Guardian.com

0 Comments